Few in the recording industry have a pedigree like Ian Charbonneau. The son of Le Mobile founder Guy Charbonneau, Ian literally grew up in the trade and began taking an active role in recording at an early age. He has since become a highly respected engineer in his own right, working with such musicians as The Rolling Stones, Garth Brooks, Eric Clapton, The Offspring, Andrea Bocelli, and countless others. Now, after working with his father for more than 30 years, Ian has struck out on his own, forming a new company, The Recording Project, for which he has developed a special 64-channel fly-pack that lets him set up shop in any venue in the world. We sat down with Ian recently to discuss this new venture, the tech behind it, his life within the business, and his approach to capturing the most dynamic live recordings possible.

You went on the road with your father Guy and Le Mobile as a young child and picked up your own gigs as a teenager. Can you tell us a bit about your early life and how it shaped you? When did you know that you wanted to make a career of recording music?

I was very fortunate to grow up very immersed in the world of audio and live recording. Having my father’s Le Mobile remote recording studio parked in the driveway of the house, my childhood world was quite exceptional. With techs often working in the garage fixing gear, artists, producers and engineers would come to our home to work in Le Mobile on their mix or project. I started going out on recording gigs with my father around 5-6 years old to my earliest recollection, from the Montreal Jazz Festival to visiting Deep Purple’s album recording in a Vermont country estate to the recordings of some Grateful Dead shows in San Francisco. I’d regularly visit the warehouse at Audio Analysts sound company where Le Mobile would often park in between projects. I would run around the warehouse playing with all the gear, the big S4 speaker cabinets, racks of Phase Linear block amps and custom consoles. On occasion, if I behaved good, I’d be allowed to take 24-track analog tapes out of the vault and make myself mix tape cassettes in Le Mobile. Those were all toys that would make me dream all day long.

Later in my teen years, when my father relocated Le Mobile to Los Angeles and purchased well-established Leeds Rehearsal Studios, which was a staple in the music production industry at the time, it became my new playground. The studio consisted of 3 soundstages with professional PAs where artists would come write songs, prepare their albums or tour preproduction. It was the home for so many musical greats, such as Toto, Van Halen, Madonna, Michael Jackson, Ozzy Osbourne, Johnny Hallyday, Tina Turner, Rick James, Dr. Dre, just to name a few. Every day was just a big house filled with talents. I quickly learned how a console and PA worked there. As a kid, I was so very consumed by anything speakers, wires, microphones, stereos and music. I would listen to all those cassettes of shows my father would bring home after a project over and over again, it seriously fascinated and consumed me. What these recordings conveyed often gave me goose bumps. What an exceptional environment to grow up in.

In my early high school years in Montreal I was very fortunate for my school to allow me to do projects on my own rather than some of the PE classes, which I couldn’t participate in as I have a bit of a visual impairment. I engaged myself instead with recording the school band, doing live sound at events and even making a school film. I always liked to be outgoing and doing creative things. I’d get the school janitor to pick up the big JBL 4333 Studio Monitors my dad had left behind at home to run live sound at school events. At age 13, I started to skip school after getting invited by my best friend, who lived across the street, to run live sound and lights at his private school talent show, which went great and led me to do more shows at other local schools. I’d charge them $1,000 to rent a PA with a big, very heavy Yamaha 1532 console, S4 speaker cabinets and wedges, some par lights and dimmers rented from Solotech. I’d keep $150 for myself and run the whole show. I was just a kid and had no idea what I was doing but seen enough PA gear and lighting being set up that I got by and learned a lot that way, the hard way. I did burn down a few woofers in the process.

At 16, I got hired to work as part of the technical production team of the Montreal Jazz Festival as sound technician to do show setups, as well as landed a job at Solotech as a sound tech in their shop. Around that time, I started to turn and immerse myself into recording local band demos and producing small album projects, also working for my father on Le Mobile as an assistant engineer running the tape machines or as a stage A2 setting up audience mics, which led me to relocate to Los Angeles and work at Leeds Rehearsal as an audio engineer. I followed my road and passion. One of my biggest wishes growing up was the hope to someday allow others to feel the same chills I had as a kid listening to all those live recordings. So to go back to the question, being so immersed in live sound, recording live shows and music, it surely without any doubt greatly shaped me and who I am today. This has been my entire life. There was never any question in my mind as for what I wanted to do in life. I consider myself extremely lucky and fortunate to this day to just follow my path and passion, though it is not always as easy as it may seem.

You, no doubt, have many great stories from your long career on the road working with many of the world’s top musicians. Are there one or two moments you could share with us?

That is the toughest of questions. Every project is memorable in some ways and you are only as good as your last gig. Just for instance, my last gig was very memorable: recording Santana with Eric Clapton or ZZ Top at the Crossroads Festival. That was pretty cool. A good engineer friend of mine always says, “Oh that story one day will be worth just about a cup of coffee” – better keep on working. I always laugh at his quote. There are so many stories to tell in the appropriate moment. Too many moments engraved in my mind over the years, it would be really unfair to name just a couple, but some definitely stood out and there’re many funny stories from being a kid growing up in this crazy business. Around 10 years old while out with my father on a GratefuI Dead recording, I decided to re-mike Mickey Hart’s drum set while the band and crew were out to lunch. I broke the all-time sacred Deadhead rule of no one allowed on their dark stage. I got caught by some techs and told them I didn’t think the drums were miked the way my dad would mike them. Oh, did I get in trouble. The dead engineer and producer John Cutler would still talk and laugh about it years later.

You have stressed the importance of having space in sound. What does space bring to the music? How do you create and capture that space when recording?

“Without the rays the sun doesn’t shine.” Think the same for space and sound. To me the dimension and space is very important when capturing sound for a recording, and as important when mixing. Space in sound, dynamics is what helps carry and trigger the emotions that music can convey. Space is extremely important in conveying the emotion that is carried by a song or piece of music. We often forget that music is essentially feel and emotions. Space in sound allows for that feel and emotion to flow smoother and make things sound better. When recording, respecting the space is crucial to capturing great sounds. Dynamics in sound, headroom, space are all very influential factors in capturing a great recording. You use a microphone preamp and microphone just like you’d use a microscope. You focus on what you want to capture. With that said, there are different kinds of applications that may change what your focus is in a sound capture that will affect your focus and how you dial level on a mic preamp. For instance, a sound capture for live sound reinforcement or PA application in a concert venue setting, you’d want to focus much more on getting a direct signal that will be amplified in a PA hung 100 feet in the air. You may not want all that space in contrary to the application of recording. That space in and around the sound that you focus on dialing your mic preamp is the key to a great-sounding recording. I feel the idea or approach in producing a live recording is much more like capturing an ensemble, a space and a moment. Having mic leakage is not necessarily an enemy but can surely be used as a tool in many cases, it is often part of the ensemble. The performance, the audience, the space and all are important parts of the equation. When all the elements are right and the moment is there, it can really create magic and the sun just shines! With all that said, I strongly believe a PA recording is great for virtual soundcheck but the PA digital audio feed is not the greatest way for capturing or recording music for perpetuity – you often end up with a hot recording harsh sounding with everything in your face, no space, no dynamics or dimension. Where do you go from there trying to mix? There is nowhere to go or no way to back out to get that space needed for a great-sounding recording. I also do not think it is a respectful way to capture music. Just because today’s technology allows that, it’s not the right or best thing to do.

For your new venture, The Recording Project, you have created a custom recording fly-pack – a 64-channel recording system that you described to us earlier as “the first fly-pack that really flies!” What’s included in the pack and why is it such an integral part of your work?

I built my recording fly-pack as one of my work tools like a photographer carries his camera. If a project allows or requires a remote truck or studio setup, I am flexible and well-experienced for that too. The fly-pack allows me to offer clients, producers and artists a much simpler and economical way to capture a live performance the right way that includes all my experience in capturing a great-sounding recording. My fly-pack is custom-built around a DirectOut Technologies modular audio converter, the MC Prodigy, that is fitted with 64 channels of their high-end MicHD preamp cards, which gets converted into digital MADI streams feeding 2 fully redundant Avid HD MADI Pro Tools systems. All of which is tidily custom-packaged into flight cases. I’m a minimalist. Less is more and best. My system is really plug-and-play. I built this recording fly-pack primarily for having full control of the recording process for all kinds of end products. The system can take 64 channels of audio, weighs less than 400 pounds to transport, fitted in 5 flight cases that can be checked in as luggage at the airport. That’s pretty cool and still amazes me to this day.

What other gear do you take on the road? With limited space for equipment, how do you choose the microphones to pack for a particular gig?

The fly-pack includes 2 utility cases for fiber cables, microphones for audience capture, some hardware, clamps, adapters and tools, everything that is needed to have a great gig. As I like to keep the system flyable I will advance as needed and make arrangements with the production sound company or venue to provide an adequate analog split as well as accommodate if any additional gear is needed for the project, which a lot of these sound reinforcement companies or venues already have on hand. I always carry with the system a versatile array of microphones to cover ambience and crowds, many of which are some great-sounding Audio-Technica microphones such as AE5100s, AT4022s, AT4021s, AT4050s and several pair of versatile A-T shotgun microphones, including the AT8035, AT8015 and AT897. A few months ago I did an Atmos project for Dolby Laboratories, so I put together an Atmos-specific microphone package that I can offer to clients as an option for which I rely on many of the great A-T mics as well. I think it’s pretty cool to say that some of my first microphones I owned as a kid were some Audio-Technica ATM41s and ATM63s. Very proud of using some great A-T mics still today. I also carry and use ATH-M50x headphones in my fly-pack.

AT4021 and AT4022

What made you build a recording fly-pack rather than a mobile studio in a truck like Le Mobile?

First, never say never, but today the responsibilities of being a truck owner are way beyond recording music. The economics of today, the kind of work that requires a truck also plays a big factor in my decision to focus on a portable fly-pack system, but most of all focus on myself and what I have to offer, which is way more important than just gear. The cost of building a mobile studio infrastructure, travel costs and responsibilities of owning a large truck or vehicle are very substantial. There are many great mobile recording trucks out there with a very limited pool of work. There’s also the cost of audio gear and very short life span of today’s digital gear. You buy a digital console for $100K, within 5 years it is obsolete, without any value. The Neve console in Le Mobile has more value today than when purchased new by my father. With today’s fast-paced technology changes I think having a fly-pack is much more versatile, flexible, budget-friendly and can offer great-sounding results.

Digital technology has greatly expanded the options available to professional engineers and amateurs alike. In your experience, what are the benefits and drawbacks of working with this technology? How has it affected your work?

A PA digital feed, whether MADI, Dante, Ravenna, or Milan, remains a digital feed for which you have no control over gain structure of initial sound capture. It might be very attractive monetarily or logistically for a production to use a PA digital audio feed to record a live album or for a video shoot. However, the end result in most cases does not advantage anyone in achieving the best-sounding recording. The approach between a live sound capture application for a PA versus recording is very different. The key to a great-sounding recording lies in having control of your mic preamps, but also the digital conversion quality and clocking all together is a very important factor that’s often getting forgotten. Digital audio technology have greatly advanced and improved, especially in the last few years. Better converters, better clocking, better computing, better plugins, and digital mic preamps all have greatly contributed to this advancement for professionals and amateurs alike.

Can you tell us about some of the projects you’ve recorded with your new fly-pack system?

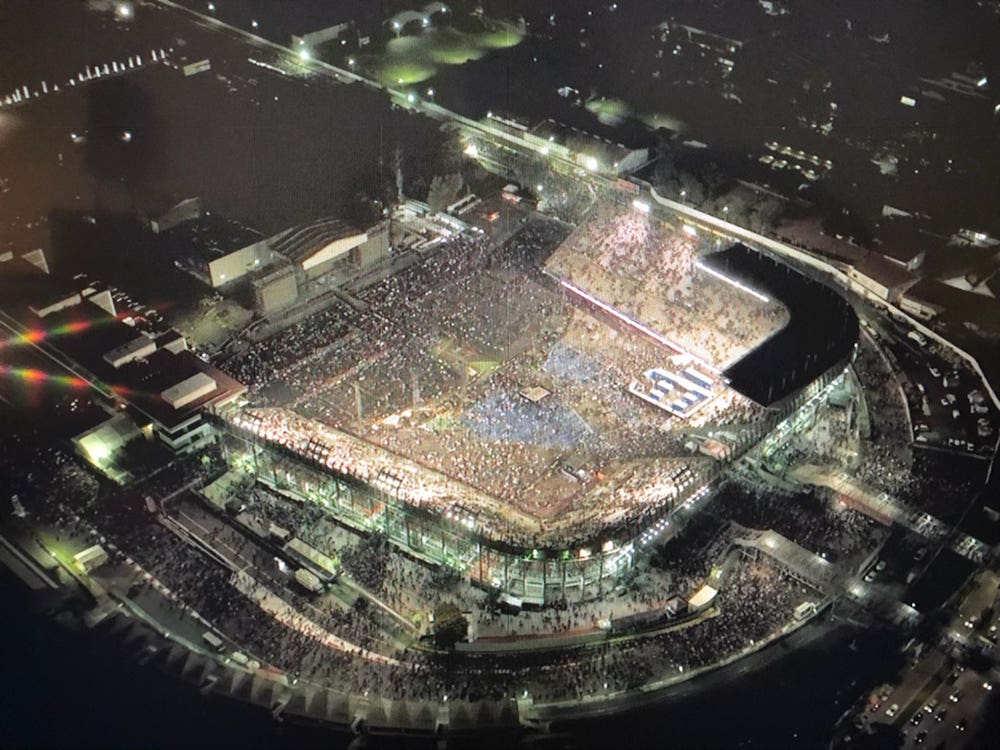

My fly-pack system was just used to capture the G3 Reunion tour with Joe Satriani, Eric Johnson and Steve Vai for a live album project and documentary film. I also had the great honor last fall to recording the “Stand for Peace” live music video released by Neil Young. The system was also used on the Eric Clapton Crossroads Festival at the Crypto.com Arena in Los Angeles to capture the 2 satellite stages with performances by artists such as Sheryl Crow, Eric Gales, Taj Mahal and Gary Clark Jr., while I also engineered the B side of the main stage in the M&B Audio truck with my father recording the A side of the main stage in Le Mobile. In addition, I’ve recorded some stadium shows for the band Maná in Mexico, as well as various live-recording projects with Imagine Dragons, Melissa Etheridge, and Macklemore to name a few. With all these great projects of the last year and a system that’s proven to be a great workhorse. I’m hoping to grow the system to 128 channels within the next year.

For more information, please visit https://www.therecordingproject.com